I love Shonda Rhimes. She is a Titan, as anyone who has seen her amazing TED talk will attest. A mega-God, a master of words and someone who has found and lost her spark in her career.

Shonda is a showrunner responsible for creating TV including Grey’s Anatomy, Private Practice, How To Get Away With Murder, Scandal. She is also, though she doesn’t know it, entirely connected to my first maternity leave, in a way which will bond us together forever, and one of the reasons I wrote this book.

Back in 2007, where I slowly realised what the juddering aftershocks of birth would actually look like, I lost myself too. I bundled on in a haze of PND and PTSD, punctuated only with madly loving my son, and a restlessness about the world because I felt like everything needed to move on, was moving on, but I was still stuck, standing in the labour ward not quite sure what the hell had happened to me.

But even in the midst of trauma, even when the world as you perceive it, the trajectory of your life, is standing still, there is movement all around you. And nothing epitomised this more than my son. Who screamed and grew and shouted and refused to sleep with a glee as brilliant as the busy sun. And also episodic US network television drama. Which churns out episode after episode.

I had practical problems. I was stuck on the sofa because my body leaked a lot, so I was always afraid of standing up and wetting myself, and also my baby was an excessively and exceptionally poor sleeper. I was beyond tired all the time. I caught up on half dozing and breastfeeding by sitting on the sofa. A friend suggested that to improve my mood I could actually watch TV rather than staring at it, and I soon found that Grey’s was an excellent place to start.

Its emotionally wired storylines would give me a socially acceptable reason to sob – as I could pretend it was about McDreamy, or George/007 – and also, somehow, with the mechanics of crying, allow me to exorcise some of my upset too. I could do my day’s crying, turned on like a tap, and it was better to do it there on my sofa than in a coffee shop hemmed in by buggies and nervous new mum friends, never sure what would come out of my mouth next.

It was distracting, reminded me of real life beyond and before kids (back then, Meredith and co were not tied to families as they are now).

It had a clear beginning and end point, with handy VO that allowed my sleep-addled mind to follow multiple narratives in a way it couldn’t always in real life – where a two-shop shopping expedition or a more than 3 point to-do list was almost always too much. It encouraged me to lock onto the theme and focus just enough to keep me sane.

And it felt like home. I also wanted to ‘dance things out’ and look to the sun. To drink with my friends. To remember (and keep remembering in hard times – isn’t that the trick?) what it was, how it was, who it was to be me.

So I feel connected to Shonda. Hardwired into that world she made.

There are two other reasons too. One, when I start writing about that time and piecing together my memoir from fragments of memories, hospital letters and old sicknotes, emails and endless half filled notebooks I’m thrilled to find she had written a memoir herself.

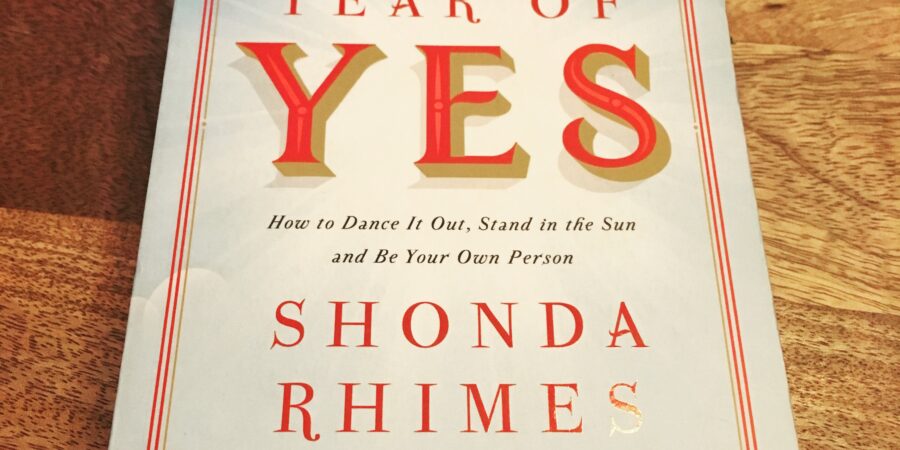

The Year of Yes. It follows her as she learns to face down what she fears, when despite her enormous professional success and prowess, her wise little sister (and I too have many of these) points out she doesn’t say yes to things, she hides from what scares her. I usually say yes, but then panic, but even I found writing and pitching a book about being ashamed and incontinent a bit testing.

So it feels fitting to read about what she learned by being bold when I wanted to start writing, properly, and was beset by angst about whether I could or should expres myself, and follow my crazy demented plan to write a beautiful and poetic and angry and political (and hopefully funny and interesting too!) book about a taboo subject.

And it did help, not least to read about her different – but also life changing – car crash into motherhood, her struggles to know herself, to admit what she wanted and needed, to find help even, in order to preserve and protect not only those she loved, but herself too.

The Year of Yes is a salient reminder of what links us together, what friendship and family are for, and that you can have confidence in dreams, however ambitious, hungry or unlikely they are. And reminded me to be thankful for my own take on her ‘Ride Or Dies’, the friends who never batted an eyelid when I wanted to write 80000 about my broken fanny.

And two, just as I was getting down to the most extreme descriptions, the hardest issues about body parts and squeamishness and the cultural cowing of women, the shaming of them and their reproductive organs and makeup, I found I could cite her, as a trident riding in on the new wave of cultural feminism, demanding to be heard, by popularising the term ‘vajajay’ and getting female orgasms onto primetime Thursday nights.